How the Heck Do You "Learn A Song?"

Musings and insights into what goes on during the troubadour music-learning process...

Investigating or discussing how troubadours learn songs is hardly a topic where anyone is likely to publish a scientific study or do laboratory research, so my thoughts and observations as a skilled practitioner might have as much value as any other resource. There are no loud or well-funded voices weighing in on this subject; high-visibility musicians are generally silent about helping others learn to play, unless it involves something they are selling. The government has no office of Troubadour General to issue advice or recommendations, schools are deeply invested in antiquated methods of music education, and corporate America would rather that you buy electronic gadgets than play music to entertain yourself.

Those of you who know me as a performer or recording artist may as well know that I have an eternal soft-spot for helping beginners play guitar, dating back to my first college textbook manuscipt in 1980 that became the Modern Folk Guitar book, the standard college textbook for beginning folk guitar. Another binge in thinking on this subject in 2006 led me to spend over a year making the epic 4-CD boxed set The Song Train as a resource to assist beginning guitar players by steering them toward simple but respected songs to guide them. I decided then that the best thing a beginner can do is to get familiar with songs that are living & breathing good songs, but musically easy. On the Song Train web site during that era I wrote an essay that you might find worth reading also. I've done a lot of thinking since then, and watched my kids growing up, which has helped me see the guitar through the eyes of other people.

I started strumming chords and playing songs on the guitar when I was about 14, and I have little memory of what it was like before I could play a song, nor did I have even the slightest understanding of my situation at the time. Once I learned how to play some songs I also quickly lost any ability I had to see what non-players see of the process from the outside. Now almost 50 years later, I am struggling to deconstruct myself to try to get an understanding of how we learn to play, in order to assist others on the path. To articulate the idea of what a song is and how we internalize it to play it ourselves may seem esoteric or even absurdly "non-academic," but I find it exciting to try to discuss what feel like vital issues, since I don't think that the average person who wants to learn to play some home-made music has a clear concept of what they are actually supposed to learn to do. Some understanding of how we musicians conceptualize, learn and play songs might help immensely and help people let go of erroneous ideas they may have been fed about "learning music."

Now in my latest era of trying to help beginners, I am working with the hypothesis that there is not something wrong with the 95+% of people who fail to get going when they try to learn to play guitar, but perhaps there is something wrong in the world of guitar education. When a system fails nearly everyone, it needs to be questioned. This isn't Navy SEAL training- it's campfire guitar, and anyone who wants to participate should be able to at least learn a few songs and have a good time doing it.

There is a wall that stops most people, and it seems to involve mastering the basic chord changes with the left hand. If you can't do that, you can't play a song. It's a lot harder than people have been led to believe, and has to do with sore fingers, coordination, hand strength, how thick the strings are, and very little to do with musical talent. Mozart wouldn't have been able to play a G chord on his first day either. But when people hit this wall, they give up too soon, and are too quick to blame themselves for being non-musical. I am convinced that they would do better if they had been confident that they were musical enough to do it, better aware of what they are trying to do, and not misled into thinking that it's easy to do by thousands of "Play Guitar In One Day" (or in 30 minutes) web sites and ads they have seen all their lives. There are also new ways around this wall, such as my Liberty Guitar Method, that allow people to skip that annoying and painful step and get right to the music part.

All my life I have encountered a steady stream of people who "took guitar lessons" or had their children do it, and after months of effort and hundreds of dollars they can't even play a single song. I always hear the same story about how they tried and failed and the "I guess I didn't have any musical talent" phrase invariably pops up. (Not to mention all the painful pressure from the parents who were paying for the lessons because the kid said they wanted to play guitar.) My wife is a fiddler, and she and I are equally flabbergasted at all the fiddle students we meet who can't play a tune, sometimes after years of lessons. Yet it doesn't require musical talent to learn to play functional recreational campfire guitar, or to master a simple nursery rhyme to sing with the kids, or to play a simple tune from beginning to end. Are all these people broken or un-musical, or have they been led astray? I have always said to people that I don't teach guitar because it would be like a skinny person teaching non-skinny people how to lose weight. I never had the problems that seem to stop most people. Let's lift up the hood and look inside.

There seems to be something even bigger going on: that perhaps people who feel the pull of wanting to play music don't understand what they are supposed to learn, and their guitar teachers somehow don't seem to understand or remember how they learned, or what they are really supposed to teach. (Most of them feel guilty because they can't read music either, and a lot of good players try to teach by methods they didn't even use, thinking they are doing the right thing.) The music education world still cannot wrap its mind around or accept the ways of the troubadour, even though the guitar has been the dominant instrument in our culture for over 50 years. Music teachers still often rely on reading music, which for the average person is useless for guitar, and even the way they teach music theory concepts is often based on the piano, which works very differently than the guitar. The "classroom learning" model is always hovering outside the door like a wolf, with notation and homework and all that other ugly stuff. The institutionalized methods of music education we use are essentially Medieval, and not much different from what was done 500 years ago in the days of Martin Luther. The "musical monks" learn from previous monks, and train the next monks to teach more monks, without ever publishing the Bible in English so the common man can read it. Homemade music should be a refuge from guilt and structured learning, and like cooking or camping, and I swear it is something you can learn joyously by doing. We could really use a musical Martha Stewart, who could show people how to do things themselves. I'd prefer that she had a personality more like Willie Nelson, though...

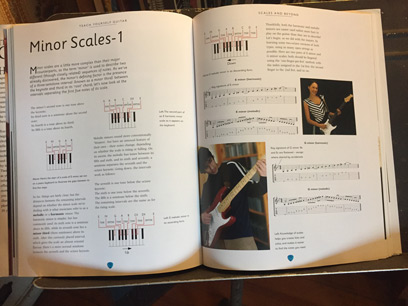

I have a pretty good-sized collection of guitar instruction materials, and must say that after a more recent assessment that I am no more thrilled with what is out there to guide people on their guitar journeys than I was in 1980 when I started writing what became Modern Folk Guitar, the first college textbook for folk guitar. Guitar hasn't changed in the last 30 years any more than it has in the last 300. It's still those six strings tuned to those 6 notes, and to get the chords and songs out of it you have to do the same things they did in 1817 or 1717. G chord. E chord. D7 chord... (there are 15 of those basic chords you have to learn.) I particularly remember being jolted in 2009 when I bought a copy of Nick Freeth's gorgeous Teach Yourself Guitar book at Barnes & Noble bookstore.

It is probably the best-looking guitar instruction book I have ever seen, with fabulous photos and diagrams, thick and shiny paper, and a nice clean layout. It seems to cover all the topics: types of guitars, music theory, basic chords, scales, barre chords, etc. I didn't even hit me right away what was wrong with it– that it was just information, there was only one mention I could find anywhere of playing music or songs, which was on page 119, and that was a brief mention of a song I never heard of. As if playing guitar was just the task of learning a body of information. This would be like learning a language without ever trying to say something to anyone, and just doing exercises and lessons by yourself in private. Doesn't seem right, does it? It just never mentions playing songs.

I did some research and found out that Freeth has no particular credentials; he is an amateur musician, and not an educator either. That really got me thinking. But I'm sure his books have outsold mine, but there is no committee or review board anywhere blowing the whistle when anyone publishes a guitar instruction book that isn't ideal. Guitar education is a free-for-all, and there are no rules, licenses or regulations. You can't nail shingles on someone's roof without a contractor's license, but anyone can hang a shingle and become a guitar teacher or publish an instruction book instantly, with no questions asked. (Not that I am hoping we get some government regulation. I just don't think the average person trying to learn guitar understands what a "buyer beware" world it is out there.)

Freeth's book and others like it have at least stopped urging people to read music on the guitar as the path to learning to play music, but they have fallen into another tiger trap. They imply that you can and should somehow "learn to play the guitar," and that will then give you the "tools" and "knowledge" it takes to then play the songs you might choose. It makes intuitive and logical sense. Learn about types of guitars so you can choose one that suits your purposes. Then learn scales and chords so you can play songs that use those scales and chords. It's logical. It works perfectly for a book, and when you thumb through a book like Freeth's it looks great, and maps out organizationally beautifully, with chapters and sections seemingly addressing all the relevant issues. I can totally imagine people deciding that they just need the information and they can learn to play. And I would bet a sizable amount of money that it would be possible to obediently go through the book and process and learn all the information and skills and still not know how to play a song, or how to learn one.

Learn strumming patterns, then start strumming and look for songs to strum, right? Unfortunately I think the whole process works the other way around, and that this approach, however logical, is backwards, and not the way people actually learn to play music. And I guess you can tell by my negative tone that I don't think it is how you should learn. We only really learn a language by trying to communicate with other people. This is a pop-culture reference book, not a guitar teaching method. It's by trying to play music and actual songs that we best learn to play an instrument. Drills and exercises may be helpful, but by themselves they are not enough. Songs are not just helpful-- they might be the only thing that matters. Sports people might see parallels here with how we might learn to play baseball or football by actually playing and trying to win the game rather than just doing drills. But how do we learn songs if we can't play an instrument, and how do we learn an instrument if we don't know any songs? It's a chicken and egg problem. Let's try to hold this thing up to the light and maybe we can pull it apart.

How do we learn songs? Who determines what is the right way to learn? How do we musicians do it, and how does or how should a beginner get started? These are good and vital questions. It seems to me that learning to play music is vastly more than just accessing a body of relevant information, and the important stuff you need to learn from musicians, not from instructors or simply information sources. I learned to play by repeatedly strumming chords and performing simple songs that I knew, that because of my lucky placement in history I happened to already have in my head. I think you basically have to "know" a song before you can "learn" it. I think that by far the best music teachers are songs you already know and are hot to try to learn. Hopefully they are reasonable songs for a beginner on guitar.

The idea seems to have taken root that you repeat your lessons over and over, and somehow, like a butter churn, if you just crank long enough, there is beautiful butter. When do the lessons become music that somebody wants to listen to? Isn't it just some effort and perseverance and discipline, plus that thing that we imagine is needed, "musical talent," we can plug into "guitar lessons" and get going. Right? Whoah... Not so fast. You can play scales forever and it'll never turn into a Bob Dylan song you can sing at a party. If you study the progression of ideas in all the folk guitar books, there is nowhere where the plane takes off and the music begins.

Without resorting to asking random people to fill out a survey, I am assuming that:

1) Many people can tell to look at guitar strummers that what they are doing is not fundamentally that difficult. There are so many "non-virtuosic" players out there that deliver songs just fine without many guitar skills, that it must have crossed most of our minds to imagine ourseves learning to do it. You learn some chord fingerings, then if you can generate a rhythm somehow with your strumming hand, and change chords at the right time to match the chords of a song you know and like, then you can sing the song. That's it. (Unless of course the chords you are playing are putting you in a key that's too high or too low for you to sing in.) It's like rubbing your stomach and patting your head to 1) sing the song 2) strum a rhythm 3) change chords.

Even though it's multi-tasking, compared to that quarter rest/clef/keysignature piano stuff this seems easy and simplistic, which may be why "folk guitar" or "campfire guitar" as I like to call it gets so little respect in music academia. It looks like fun, not something you major in in college, and gets the hackles up of career educators who believe that "true learning" involves healthy doses of things like "hard work" and "discipline" as well as "testable" information that can be used to assign grades to students. I will come back to all this...

2) Many people seem to have an internal barrier or a series of barriers that keep them from just going out and getting a guitar and teaching themselves. A huge number of people have gotten hold of a guitar, but abandoned their efforts for various reasons and at various places in the learning process. Maybe it is not that easy, and maybe people just don't quite understand what they are trying to learn to do.

These barriers also seem to involve thinking that people:

• ... mistakenly think they lack some essential ingredient that we’ll call “musical talent” (for lack of a better name), and tend to blame their failures on their lack of this ingredient. I blame the way music is taught, not the people who want to play some. I think that far too much of music education is mired in 500-year-old ideas that have minimal value for modern troubadours. Far too many people have been convinced that they are not musical by previous bad experiences.

• ... are reluctant, unwilling or unable to teach themselves, or are not used to self-learning even when it is the best way people learn certain things. They have heard too much of the story about how you learn music, and like Occam's Razor it's easier for people to accept that they are not musical than that all the music lessons, music classes, TV and movie stereotypes about music learning, and school choir experiences they have had did not prepare them for the task of how to learn to play a Johnny Cash song on a guitar.

• ... can’t wrap their minds around the learning process enough to begin, since the path by which we troubadours learn songs is either too vague, or too far from what they have been told is how music learning happens. A huge number of people have been led to think they need "guitar lessons" that involve notes, rests and treble clefs.

In my large bookshelf of guitar instruction materials I have never even found so much as a sentence that discussed the learning process itself, abstractly, about how the millions of us who can play actually get those songs to come alive within us. What pulls us forward into and through the guitar learning process? It's not really a step-by-step, academic subject suited to the classroom learning model, that seems to be the default in education today, now that the time-honored apprentice system has evaporated. I can’t describe the real process scientifically, but I can shed some light on the subject and illuminate some aspects of it. There is a strategy of sorts that is described or implied in nearly all instruction books, which is that you follow along somehow with notes, TAB or strumming patterns and somehow that turns into music. I say this is not at all how it happens in the world of the modern troubadour.

Some other issues are also involved...

• The internet and even a music store’s wall of guitar instruction materials are unfortunately overwhelming, confusing and contradictory, with all sorts of products declaring loudly that they are the best and easiest way to learn. I also suspect that more people would teach themselves to play if they had a feeling that they were allowed and encouraged to do it, and if they had a better map of where they were trying to go. If you thumb through guitar instruction materials you just don't get a sense of how the learning process unfolds. The typical beginning folk guitar books jump from a simple fingerpicking pattern to alternating bass and sinple melody in a few pages, when in real life that process takes years. So perhaps as much as assisting other people in their learning, my role as a tribal elder here might be as much to try to give people permission to do some things and to help them understand that they may be already on a reasonable path. None of us like the feeling of digging in and applying ourselves to something only to find out we were doing it all wrong.

• Can you learn something properly without first having an understanding or visualization of the learning process? Can you really learn something properly and deeply without joy or passion? Do you ever really learn to read until you find a good book or article that pulls you in and captivates you? Do people win races who don't love to run? Would kids bother to learn to ride a bike if it wasn't totally fun? These kinds of issues should be addressed in music education, but I don't see that happening much.

Rote learning and much of what passes for public education doesn’t really pass this kind of test. My kids in elementary school don’t have a clear vision of why they need to know what 8 times 7 is, though no doubt if they had a motivation they would learn better and faster. Learning to multiply so as not to fail in school or to not disappoint one’s parents is a much different motivation than a life situation where a student might be counting tomato plants or fishing lures and really wants to know something that involves using multiplication. I can’t weld, but I have an understanding of how I would probably need to learn. I can’t play lacrosse either, but I can understand that I need a lacrosse ball and a lacrosse stick, and that I need to spend hundreds of hours tossing it back and forth with someone else as I learn to throw, catch and pick the ball up off the ground, as well as learn the rules of the game.

I am also reminded, as I ponder the process by which we get musical ideas and skills into us, that my children and their friends love to go to an indoor "skate park" in our area. It's a big building, crammed with ramps, halfpipes, bowls, rails and other sorts of equipment that skateboard, scooter, rollerblade and BMX bicycle people like to play on. At any given time there are 30 to 100 people, ranging in age from 5 to 45, whizzing around, each immersed in their own personal journeys as they demonstrate or work on various moves. It is a place of intense learning, yet there are no signs of teachers or instructional materials of any sort. All the kids are joyously exerting staggering amounts of energy, learning skills and confidence, facing their fears at the top of steep ramps, watching each other. It's a nearly utopian world, and it is the kind of thing that has created Olympic athletes like Shawn White, and rocketed freestyle skiiing, snowboarding and other highly acrobatic and difficult sports to the center stage of athletics. Yet the kids are teaching themselves and each other. I have trouble "teaching" my kids to do anything, but I can't stop them from learning in the skate park, and the only struggle I have is getting them to stop. Guitar was like that for me when I was 18, which is why I am good at it. But when I try to "teach" someone to play, it's always a struggle to get the motivation going, and to find that place of joy that has to be there for progress to happen. We do best in a "learning environment."

I can imagine that when Louis Armstrong was a kid in New Orleans, lots of other people were wandering around the streets with their instruments, watching and participating in a musical free-for-all of street, church and tavern music, not unlike a musical skate park. Also not unlike the "total immersion" French language learning that happens when you go to France rather than read a French instruction book or take a class.

• If you want to learn to play a song, it would also be a good idea for you to observe as many people as possible playing that song. Or even just one good one to use as a model. The best way to get a lot of knowledge into us properly, including troubadour music, is through repeated listening or watching, followed by repeated doing. Monkey see, monkey do. When any of us sing Happy Birthday or some other song we “know” and can spout out, we are not reading anything, or doing an intellectual act of any sort. We know it and we sing it, though we may have trouble starting on a good pitch for the starting note, and as a result we may have trouble singing the highest or lowest notes. (People who sing without instruments, you may have noticed, always have someone feed them a starting note or chord of some kind before they sing, to get the song at the right pitch.) I’m not sure if the idea of the pitch of a song is something that a non-musician knows about and understands, though I am assuming that a non-musician reader can at least fathom the idea. It seems to be an axiom of some sort that every adult would have had some experience with the idea of high notes, low notes, and vocal range of a person or of a song. I recall reading that there was a recent study where average non-musician people who were familiar with and liked pop songs instinctively sang them at a pitch very close to the original pitch of the hit recording, even if they considered themselves to be lousy singers or totally un-musical.

• YouTube to the Rescue? Luckily, people seem to be learning a great deal from YouTube videos now, so it's already becoming more of the monkey-see, monkey-do process that it should be. Unluckily, there is no regulation or rating system, and there is so much incompete, poorly thought-out and downright wrong and bad information out there that you need a teacher just to tell you if things are to be trusted. The online world of beginning guitar seems to us serious players to be quite cluttered with hucksters just trying to get clicks on their sites, and what seem to be well-meaning amateurs who are bent on becoming spokespersons for something they don't even do very well, and know little about. Maybe they are clogging up the learning world, and maybe they are un-knowingly (but helpfully!) spreading the idea that it takes a while to learn. Their clumsy playing might be helpful to other beginners who don't realize what their own learning path looks like. Sometimes you can learn better from another beginner than from a master.

Luckily, the almost 50 years of obsessive overdubbing and studio production inspired by the Beatles is winding down, and the idea of recording "real music" and more live performances seems to be catching on steadily. Add to this the fact that the new "gold standard" of reality on YouTube is a single, wobbly camera or cell phone video that purports to capture something that is "actually happening." When this involves people playing music I am thrilled. What I am hoping for is that YouTube will lead to people who want to learn to play a song simply being able to watch other people play it, and not a bunch of lessons & curriculum.

So what is going on in recreational guitar? What are we trying to learn?

How do we learn it? What is the information we are internalizing when we learn songs? How do we get it into ourselves? What do we do first? What does the path look like? Are there yellow bricks involved?

Presumably it unfolds differently in different people, but there are patterns and tendencies. When Woody Guthrie sang a song with his guitar, or when any troubadour-type musician plays rhythm guitar and sings a song, it is a fundamentally different thing going on than when a church organist plays a hymn or the school music teacher sight-reads at the piano. Johnny Cash was not reading anything when he performed. Same with Hank Williams or Neil Young, or anyone else you could possibly name. They sing songs they know from memory, songs that they created or learned “by ear” and not from reading notes on a staff. What they and other troubadours are doing on guitar is a fluid, variable thing that is fundamentally the same each time, but also depends on what the performer feels like doing at each moment. And this is what you need to learn to do also, and it's less like reading a page of a book and more like walking across the room or reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, or making a sandwich. We get in the moment and do something we know how to do according to how we want to do it at that moment. (NOTE: This is a polar opposite of the mindset that my children are put into in school music class when they are told what to sing, when to sing it, and sometimes exactly where to put their toes on the floor when they do it.) Troubadours generally play the same basic chords at the proper times in the song, but the strumming hand is likely doing some improvising on the groove, the dynamics, and even what strings are sounding.

It is my firm belief after a lifetime of playing troubadour-type music built around using an instrument to accompany and generate songs, that until you have some songs in your head that you “know” and have internalized and believe in, you will never learn to make music that has any magic in it. Music comes to us via a different path when it is performed from memory, as opposed to reading. Which brings up a huge and sore subject. The reading of music has been assigned far too much value in the world of music and especially guitar education, though of course in the specialized areas where it works, it does work for certain things.

This issue of reading or not reading music is intimately intertwined with our attempts here to articulate what happens when we learn a song. To keep from spiraling too far off the topic, I have posted more thoughts on guitarists reading music in general. The “legit” music world has had 500 years to make its case for sight-reading music, and I want to talk about the other kind, the “ear” music thing. The names I have most commonly heard throughout my life for two basic types of musical learning are “reading music” as opposed to “playing by ear.” We now probably need to add “learning by watching on the internet” to the list.

So how do modern popular musicians and performers “learn" their songs? Are we talking about the same activity as what happens when the music teacher reads the piano music so the class can sing Oh Susannah? Absolutely not. These are completely different activities.

Here is a list of axioms:

1) You have to learn some basic chords. If you can't change chords fast and smoothly enough you're out of the game.

2) You have to learn how the chords "match up" with the specific songs you want to play. Every song has its own "chord map," (or several, since there are such things as substitute chords, and you always have the right to play a different chord than someone else plays in a song, if it sounds good to you.)

3) There are 12 music keys. 12 major chords, 12 minor chords, and 12 seventh chords. Of those 36 most basic chords, you can play 15 of them without using a difficult technique known as "barre" or "bar" chords. The world of what songs can be played with those only 15 chords has been the world of basic campfire guitar for 4 centuries now. It's a surprisingly big world, and includes a massive number of popular songs, but there is no certainty that any given song you'd love to learn to sing is accessible to you even if you master those 15 chords, because it might not be in a pitch where you can sing it. The chances of a novice or beginner being able to handle the chord changes, and sing in whatever key those chords put you in are actually pretty small. Finding a song you love that isn't hard to play and that is in the right key for you can put you right in the game, however. There are lots of them out there, and you need to find at least one of them to launch yourself.

4) Then you just generate a rhythm of some sort with your strumming hand, change the chords at the right time with your fretting hand, and sing the song.

5) It helps immeasurably if you have a "reason to play." It's extremely valuable if you are in a social or church group where people are already singing together, or if you want to sing your baby to sleep, or perform at an open mike, or at a campfire with your family. Plenty of people will sing to themselves, and don't need an audience. I used to be one of them when I was young.

So we have this idea of the "chord changes" or the "chord map" of each song, though unfortunately the chords you play to the song only create it in one of the 12 musical keys. If it's near the optimal pitch for your voice for that song, you're fine, and you can sing it. Otherwise you have to get someone else to sing who can maybe sing it in that key, or you have to learn to play it in a different key that suits your voice, which might not be reasonable to do. The solution might be to learn it in another key, or it could be as simple as adding a capo to raise the pitch a few steps.

So how do we get songs into our heads and hearts? We are not all identical, and we undoubtedly learn at a different rates and in different ways. Some musicians can learn certain songs extremely quickly, and some can’t, and some of us learn certain songs and certain types of songs more quickly than others. There are no fixed rules, and the forces of memorization, desire and talent all mix together to create the results. If we hear a song every week in church, we eventually absorb the melody. No one learns to sing Happy Birthday from a book. We know it after many many repetitions, and gradually get the notes into our memories in the right places. I don't think I am a fast learner, and neither are many of my superb troubadour friends. I'm extremely good at recalling things I have learned, which is a different and equally useful skill.

If you want to learn a Hank Williams song, for example, the common troubadour approach is to obtain a recording of it, and then listen to Hank or someone else sing it, and probably sing along with the recording, (unless the singer is the opposite gender or has a different vocal range entirely) until we can reliably pull the melody from our memories. I think it has been proven that our brains generally store words and melodies together as a “chunk,” and singers generally learn the the words and melody together as a single thought, not as 2 different things. It may prove to be a frustrating experience and maybe an impossible task to memorize song lyrics without singing them at the same time. Most of us learn the chords, words and melody all together.

As I try to imagine what it must be like to look from the outside at what I often call "campfire guitar," where people use a guitar to accompany songs, I find myself pondering what the actual steps are when people learn to do this. Here is an outline of the process I think most of us follow. The song usually slowly emerges, taking shape gradually, rather than jumping out in a completed form. You don't really learn measure 1, then measure 2, etc. as if you were reading music:

• I keep saying– immerse yourself in a recording of the song as much as you can. Repetition is always at the heart of memorization and much of learning. We need to hear the song as many times as it takes for it to imprint and take shape in our heads. Also you might also want to listen to as many versions as you can find. If you are trying to come up with your version of a classic old song, there is another dimension going on, where we end up distilling down the versions of what many other artists do with a song to create our own version, that may not be identical to any one of them. We need to embed the song in our heads, to learn and to absorb the song, as well as to intake various ideas of how other artists have approached it. Being able to sing it to ourselves is a great starting point for learning to play it on guitar, though a lot of us do much better when we sing with an instrument.

Luckily we all now have easy access to recordings and headphones, so modern people can do this privately. It must have been much different to learn a song if you lived in an igloo with seven other people, with no recording devices and little privacy. People sing a lot and learn songs in their cars, and I recall reading that this is part of the reason why Americans don’t like to carpool to work. I would like to see more research on how many people sing in their cars during their commuting time. I have been asking my musician friends if they repeat the same songs over and over again while listening alone. The typical answer is always a sheepish, slightly embarrassed “yes,” as if they are revealing a private secret. I certainly do it a lot, especially when I am “hot” for a piece of music and getting ready to learn it. My wife does the same thing, which sometimes means intensely "binge listening" to a song a dozen or more times in a row.

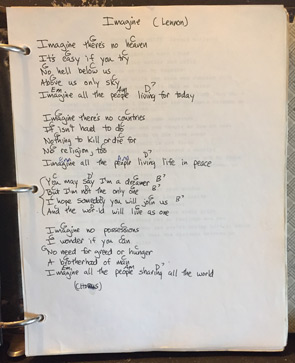

• Try to map out the key, song structure, lyrics and basic chord changes. How many verses or repeating sections are there? Is there a chorus or refrain? Where do sections repeat and where don’t they? Is there an introduction or a special section somewhere in the middle that is not a verse or chorus? I don’t want to seem like a Luddite, but I swear this is best done with a pencil and a full-sized sheet of paper. It’s often hard to lay it all out in your head, or with any digital device I am aware of. A simple country song with 3 chords and only 2 verses and a chorus is easy to wrap one's mind around, though some songs are of course much more complex than others. Here is the sheet I wrote out in high school to learn the John Lennon song "Imagine." Even then, at age 16 I seem to have figured out what to do in my blissful ignorance and desire to play songs I liked. This is "troubadour sheet music." When you think we are reading music because we have a notebook or a music stand in front of us, this is likely what we are looking at. (If not this, then a chord chart.) This song has 2 musical sections, what you might call verses and a chorus or refrain. Sing 2 verses, then the chorus, then another verse and another chorus. Musicians often call the 2 parts the "A" part and the "B" part, so the shorthand we troubadours use for the structure of this song is AABAB. The A part and the B part each have their own chord structure, as shown by the chord letters above the words in the picture.

To determine the best chord changes, you may need to spend some time listening, which is a good reason to have a physical or digital copy of the song that you can "rewind" and play certain parts over and over again. This is what a guitar teacher, song book, web page, or a mentor can help you with. (Rewinding may not be possible with digital streaming.) If the song was not created or performed by a campfire-style guitarist, it may also be difficult to make it work on the guitar, and it may be unclear in places what to do. Popular songs written prior to the 1950s were almost always written on the piano, and are often problematic for guitarists to play. It's also not easy for a beginner to come up with a solo campfire arrangement of a song that was recorded with a 48-track studio, and all sorts of tracks, horns, harmonies, strings, etc.

You may want to look around on the internet to see if there is any accurate information on how to play the song, in addition to performances of it. There are all sorts of YouTube videos carefully showing the wrong way to play things, and it's a thorny new problem that it can be maddeningly hard to find accurate information. [Try to learn to play Noel (Paul) Stookey's The Wedding Song, for example. The amount of conflicting information people have posted is startling. He did it on a 12-string that was tuned low but still in standard tuning (not DADGAD as some YouTubers say), and he also added a capo.] Different artists will not always play the same chords or even use the same guitar tuning when they each sing a particular song, and there are no rules or laws that say that you have to play them a certain way. If it sounds wrong you of course should probably change something you are doing, though you can easily find some chord changes that work for a song that may not be exactly what the original version used. You may also be able to get by with a simpler or altered set of chords that will sound OK with a song that might be too difficult when played "correctly."

There's also no certainty that the best key for you is the original key, which means you'll quite likely have to first determine the chords in the original key, and then figure out how to change or "transpose" them to a better key for you. If you are learning a song by an artist of a different gender you will likely need to transpose it. Most of us do it with a pencil, writing the transposed chords above the original ones. This is a troubadour skill we all need to learn, though it is understandably confusing to beginners.

• Put together a “skeleton” arrangement, and determine more accurately what is the right key for you. This would mean that you can strum the basic chords and sing sketchily along, probably reading the words. (You may need help from a musician or teacher to figure out the chords.) The guitar plays pretty well in 5 of the 12 possible keys. If need be, transpose the chords or add a capo to get to the best key. You may not know you're in the wrong key until later in the song, when you reach the highest or lowest note. There's no point in putting a lot of effort into a guitar part until a little later in the process. Pop stars tend to have really high voices, and might not be the same gender as you. Every song can be played in any of the 12 keys, and though the relationship among the chords to each other is always the same, the actual chord names are different for every key. If the original artist is singing and playing a G chord, you might end up playing a different chord when you sing that part of the song.

• Develop a “groove” and rhythmic framework for the song. Hopefully it would fit both the song and your guitar skills. It’s possible that this precludes many of the other steps, in that if you can’t imagine yourself generating the groove and making the song work with your guitar, there is no point in going any further.

• Put together a more complete guitar accompaniment. It may take a while to add or create picking or strumming that suits us or comes from our personal style or toolbox of techniques. Once you can get the song going, you can gradually add intros, turnarounds, tags, vamps and other elements to “flesh out” and personalize the song.

I'll discuss in some detail more about how to create your own arrangement of a song in a future post.

This is another posting where I'm trying to raise issues, questions and awareness in the world of modern troubadours... You deserve a reward or a door prize for making it to the end. Please check back to look for new posts as I get them done. I plan to cover a wide range of issues and topics. I don't have a way for you to comment here, but I welcome your emails with your reactions. Feel free to cheer me on, or to disagree...

Chordally yours,

HARVEY REID

©2016

H

H

H

H